Let’s build a good future for all regions!

Overview

The main points covered in this article are:

- Broad agreement on the TPP has been reached.

- The TPP actually does not incentivise mass migration, it is part of a process which is empowering people to live and work in their own lands.

- The TPP is part of a trend of ongoing economic development in South East Asia, Central America and South America, which is concomitant with raising wages in those areas.

- Regional imbalance is one of the core components of global economic crisis, which can be remedied by enabling people to actually buy the products they produce.

- The advent of a multipolar world means that global ideological hegemony can no longer be easily held by one regional group.

- Unlike the disastrous case of NAFTA, it is in fact strategically sound for all ethno-regionalists to endorse the TPP.

It is written with the intent of conveying the necessary information in the shortest amount of time. Read more beneath the fold.

Things are Happening

Sometimes there are really bad days, when you feel like the ball of yarn that is global trade, development, and geostrategy, is being made ever more complicated by the actions of foolish politicians.

And then there are good days, when everything seems to work the way that it should. Today is a good day for those people who have been hoping for development of productive forces to continue rapidly in Asia:

Nikkei Asian Review, ‘Sweeping trade deal sets wide-ranging rules’, 06 Oct 2015:

TOKYO—The broad agreement just reached on the Trans-Pacific Partnership marks a major step toward creating a massive economic zone along both sides of the Pacific.

The TPP is a free trade agreement that will lower tariffs and establish more transparent investment rules among the 12 member countries. It aims to promote trade and investment in the growing Asia-Pacific region.

The pact builds on a 2006 FTA between Singapore, Chile, New Zealand and Brunei. Negotiations for a broader agreement began in March 2010, when the U.S., Australia and others joined the process. Japan came on board in July 2013.

The negotiations covered issues ranging from tariff reduction and elimination to intellectual property protections and reform of state-owned companies. The agreement’s 31 sections cover those areas as well as rules governing such topics as e-commerce and finance.

The tariff cuts are expected to benefit companies by fueling export growth. Clear rules on foreign investment and dispute resolution will help smooth the flow of money and services across borders. Individuals should benefit from simpler customs procedures.

In Japan, lower import duties on rice, beef, pork and other agricultural products will let consumers buy inexpensive foreign goods more easily. The TPP will slash heavy tariffs protecting the nation’s agricultural sector, likely forcing such reforms as improved productivity and a shift to bigger farms.

With a broad agreement now in hand, the participant countries need approval from their legislatures. How long this will take is unclear. The agreement will not enter into effect until after the U.S. ratifies it, a step likely to come in 2016 at the soonest. Congress appears set to take its time discussing the TPP, addressing persistent concerns about the impact on domestic industry and employment.

(Nikkei)

The same story is being echoed almost verbatim in the Financial Times in the UK as well, with a bit of a twist so as to appeal to western liberal viewers. This is because Nikkei now owns the Financial Times.

And:

Nikkei Asian Review, ‘Japan assembling task force to aid farmers’, 06 Oct 2015:

TOKYO—The Japanese government will establish a task force as early as this week to help farmers deal with the expected rise in low-cost imports under the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade agreement.

“It’s the responsibility of politics to protect the beautiful original landscapes of agriculture,” Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said Monday night.

“I want to do my best to turn agriculture into a field that can give young people dreams,” Abe said.

Assuming that the TPP will trigger a flood of cheap imports, the task force will focus on enhancing farmers’ productivity and stabilizing their income.

Japan’s small farmers are only half as productive as their larger counterparts with 15 hectares or more of land. Key proposals include a tax system to encourage consolidating farmland and an expansion of irrigation subsidies.

The government also plans to introduce an insurance mechanism to supplement farmers’ income in the event the prices of agricultural products fall.

[...]

Now, there were plenty of people who were against the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and who argued very forcefully against it back when the TPA was being authorised so that the United States Executive branch would be capable of negotiating the agreement.

So it’s necessary to cut through some of the rhetoric that was being used back then.

The TPP does not incentivise mass migration

The Trans-Pacific Partnership includes 12 countries:

- Brunei

- Chile

- New Zealand

- Singapore

- United States

- Australia

- Peru

- Vietnam

- Malaysia

- Mexico

- Canada

- Japan

- Colombia

- Philippines

- Taiwan

- South Korea

- India (future)

- Laos (future)

- Myanmar (future)

For North Americans who are worried about ‘the threat of mass migration resulting from the TPP’, you all should know that the Trans-Pacific Partnership actually incentivises everyone to stay in their own countries, because it incentivises the movement of capital—and thus, jobs—into locations in the developing world, rather than transplanting labour from the developing world into North America. This is simple economics.

Take for example the case of the Philippines. A lack of jobs inside the Philippines triggered a decades long mass migration out of the Philippines and into the North Atlantic, to the point that almost 10% of the female population—many of them rural people—of the Philippines ended up outside of the Philippines.

The fastest way to turn that situation around is to push more FDI into the Philippines, carry out governmental reforms, and build infrastructure in rural areas. That would halt the outflow of human beings almost immediately, and would have a good effect for everyone. After all, mass migration doesn’t only hurt white people. Mass migration also hurts people from developing countries that experience the phenomenon known as ‘brain drain’, and also among rural people the phenomenon known as ‘dislocation’.

The Standard, ‘Aquino wants to make Philippines into Detroit’, 06 Oct 2015:

[...]

One major initiative is the so-called Comprehensive Automotive Resurgence Strategy program, or CARS, which aims to woo General Motors, Toyota and other auto giants to set up shop in the Philippines. It entails tax incentives and about $600 million worth of benefits for companies willing produce at least 40,000 vehicles annually, each fully built in the Philippines.

“We’re not relying on trickle down,” Aquino told me in an interview on Wednesday at the presidential palace in Manila. “We are really trying to enable our people to seize every opportunity that comes their way.”

Call and data centers have created hundreds of thousands of good-paying jobs in the Philippines. But that’s the domain of educated urban workers, not the tens of millions of rural poor; manufacturing would soak up more workers at home and hopefully draw back some of those currently working abroad. While the $24 billion Filipinos wired home last year helps Manila’s finances, migration depletes the quality of the local labor pool and hurts productivity.

“At the moment, we are a two-shop economy—business-process outsourcing and remittances,” says Nestor Tan, president of BDO Unibank, the nation’s biggest money manager. “More manufacturing would diversify the economy in so many ways.”

The challenges, however, are immense. Carmakers aren’t going to show up until the Philippines improves its ports, roads, airports and its notoriously expensive and unreliable power supplies.

Clearing logjams to infrastructure projects will be hard; paying for them will be harder. Last month, Aquino greenlighted six transportation-related projects totaling about $8.4 billion; those costs will grow exponentially. As great as the record $6.2 billion of FDI last year sounds, it’s still half what Thailand has been getting in recent years.

Pulling in more cash requires better governance. Investors will demand more progress in reducing corruption and inefficiency before deploying fresh capital. Equally important, Aquino’s anti-graft push must outlive his six-year term, which ends in June 2016. That means he’s going to have to start putting more public services and transactions online, including bidding for government contracts. He should go further to do lifestyle checks on lawmakers living far beyond their means. He also should do more to clamp down on the infamous Bureau of Customs, where tens of billions of dollars have vanished since 1990.

Still, Aquino’s not wrong to see an opportunity here. Given Japan’s aging population and the central bank’s failure to end deflation, Toyota is looking abroad and expanding its strategy of producing cars where they’re purchased. (The world’s largest automaker may soon formalize a $1 billion investment in a new assembly plant in Mexico.) Its traditional Southeast Asian base—Thailand—is looking less and less attractive as the ruling junta juggles a vague and shifting list of economic priorities. Thailand’s central bank recently downgraded the economy’s prospects this year, saying business and consumer confidence had been shaken by the weaker-than-expected recovery.

With its young, English-speaking population, low labor costs and rising household incomes, the Philippines looks good by comparison. The biggest change in the Asian manufacturing space is choice—automakers suddenly have many options as India, Indonesia and the Philippines vie for their factories. At first, the Philippines is trying to find “a niche for the region” and position itself as “a mass producer of a model that is not produced in Thailand,” before building on those gains, says Trade Secretary Gregory Domingo. In the interview, Aquino called signs that Japan’s Mitsubishi may be upping production in the Philippines “very, very significant.”

[...]

That is just one example.

Here’s another, involving the pattern in Vietnam:

Nikkei Asian Review, ‘Canon Vietnam helps itself by keeping female workers healthy and happy’, 19 Nov 2013:

HANOI—Rising wages for factory workers in China have spurred global manufacturers to shift some production to Southeast Asia, where labor is cheaper. But companies can only stay ahead of wage trends for so long. Then it becomes a matter of giving workers enough incentive to stick around while avoiding a loss of competitiveness.

Canon’s subsidiary in Vietnam has found that creating a relatively employee-friendly environment goes a long way.

The major Japanese camera and printer maker established its local unit in 2001. Today, the subsidiary runs three printer plants, staffed largely by young Vietnamese women. Yet labor costs are on the rise here, too, with manufacturers one-upping each other to secure workers. In the northern part of the country, Samsung Electronics of South Korea is aggressively courting workers with higher pay.

Canon Vietnam is taking a different approach. “We will not get caught up in an unnecessary fight” over human resources, said Katsuyoshi Soma, the unit’s general director. Instead, the company offers its Vietnamese employees comprehensive welfare and benefits. It also tries to make workers feel they are more than just cogs in a machine.

At 7:00 a.m. each day, Soma carries out a ritual started by his predecessor. He and other members of the managerial team stand at the gate of the company’s factory in the Thang Long Industrial Park, about 16km north of Hanoi. The bosses greet workers as they file in.

“The chief shouldn’t be too high up (and inaccessible), like clouds in the sky,” Soma said.

The average age of the unit’s workers is 24; 93% are women. “Their growth is directly linked to our productivity,” Soma said, stressing the importance of ensuring they are healthy and happy.

Employee benefits include pre- and post-childbirth care. Twice a year, Canon Vietnam invites a doctor to talk to pregnant women about childbirth. New mothers are allowed to leave work an hour early. The company also reserves a room for them to express their milk.

As for more general efforts, a cafe and convenience store were opened last year on the site of the employee dormitories, which are home to nearly 4,000 workers. The company also organizes monthly events—trips, sports festivals and parties—to encourage loyalty and improve morale.

All of this has helped Canon Vietnam build a reputation as an employer worth sticking with. The benefits are considered a big reason its turnover rate has declined by half. This is no small feat in a country where turnover at factories is high—monthly rates of 10-20% are common.

Still, Canon Vietnam is not immune to climbing labor costs. Vietnam’s minimum wage has been increasing at a 20% annual clip, pushing a number of foreign companies into the red. To overcome this challenge, Soma emphasizes the need for “production innovation” and “reform rather than stagnation.”

Canon Vietnam has started in-house production of some components it used to import. It has also found local parts suppliers and offered them guidance. Its local procurement ratio hit 67% this year in value terms, 15 percentage points higher than in 2009.

Soma, meanwhile, is challenging a stereotype—widely held among Japanese companies—that productivity in Vietnam is not as high as in China or Thailand. The key is to give workers a chance to reach their potential.

In 2010, Canon Vietnam introduced a qualification system for metal molding techniques. Under its human resources development program, a select few workers go through two months of intensive training in basic molding methods. “In the past, they had to turn to Japanese employees for help,” Soma said. “Now they can find and handle defects on their own.”

When Canon fired up its first Vietnamese factory in 2002, the unit had 1,100 workers. Since then, the company says its production operations have grown twentyfold, with sales increasing steadily as well. The policy of nurturing workers promises to help keep the business on a positive trajectory.

This is what happens when people actually invest in Asia. With more and more governments actually making innovation into a cornerstone, the rewards from such investments should be significant.

Nikkei Asian Review, ‘Infrastructure, cross-border connectivity vital to development’, 05 Jun 2014:

[...]

“To maintain the hard-won gains of development of the past 20-30 years, we should pay attention to stability.”

Surin said the futures of Asia’s countries are intertwined. “For Japan to address the problem of its shrinking population, East Asia will have to grow up together,” he said. “And the only way to do that is to help East Asia stand up on its own, and (for) its people to become consumers.”

The former Asean chief said: “If the 600 million people of Asean can gradually become more prosperous, with higher incomes, they will become business partners for the Japanese and be consumers of Japanese products. Japan will need more customers outside its borders for demographic reasons.” For that to happen, he said Asean member states need to invest more of their budgets in science, education and technology. “Asean countries spend less than 0.5% of their GDPs on research and innovation. We need to move away from an economy that depends on labor, and the ADB can help.”

To increase trade within Asean, the 10-member bloc will by the end of next year create an economic community with reduced tariffs. Nakao said many of the tariff issues for the coming Asean Economic Community have already been resolved. “Moving ahead, even if (the AEC) cannot achieve 100% tariff reductions, it is moving closer to a single market and is becoming a core of growth for the Asian region.”

Surin said lowering tariffs was not the only issue Southeast Asia needs to tackle. “Has Asean been effective enough in integrating?” he asked. “Most of the agreements and legal instruments to sustain this Asean economy have been done. The challenge is the nontariff barriers. How much are you going to reduce the tariffs and how much are you going to establish nontariff barriers. Some economies are reluctant to open up, particularly the big ones.”

Nakao agreed, saying, “There are many issues (that need to be dealt with), such as education, urbanization and the aging of the population. The ADB wants to address those issues along with Asean. One way to address these issues is through cross-border connectivity.”

As an example of cross-border connectivity, Nakao talked about the Greater Mekong Subregion initiative, a plan to connect countries bound together by the Mekong River, such as Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

[...]

The passage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership on top of all that, would turbo-charge the flow of more investment into places that have up until now not experienced significant enough development. With rising prospects in their home countries, many South East Asian people will make the choice to stay in their own lands as opportunities are brought to their lands.

Some have however been suspicious of this, and have put forward the idea that a US President could, for ideological reasons, use the powers granted by the TPA in order to modify the interpretation of the TPP so as to facilitate or incentivise mass migration. I’m happy to tell you that such a thing would be impossible.

There is a supreme court ruling called Galvan v. Press, 347 U.S. 522 (1954), which explains:

Galvan v. Press, 347 U.S. 522 (1954):

[...] In light of the expansion of the concept of substantive due process as a limitation upon all powers of Congress, even the war power, see Hamilton v. Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co., 251 U. S. 146, 251 U. S. 155, much could be said for the view, were we writing on a clean slate, that the Due Process Clause qualifies the scope of political discretion heretofore recognized as belonging to Congress in regulating the entry and deportation of aliens. And since the intrinsic consequences of deportation are so close to punishment for crime, it might fairly be said also that the ex post facto Clause, even though applicable only to punitive legislation, [Footnote 4] should be applied to deportation.

But the slate is not clean. As to the extent of the power of Congress under review, there is not merely “a page of history,” New York Trust Co. v. Eisner, 256 U. S. 345, 256 U. S. 349, but a whole volume. Policies pertaining to the entry of aliens and their right to remain here are peculiarly concerned with the political conduct of government. In the enforcement of these policies, the Executive Branch of the Government must respect the procedural safeguards of due process. The Japanese Immigrant Case, 189 U. S. 86, 189 U. S. 101; Wong Yang Sung v. McGrath, 339 U. S. 33, 339 U. S. 49. But that the formulation of these policies is entrusted exclusively to Congress has become about as firmly imbedded in the legislative and judicial tissues of our body politic as any aspect of our government. And whatever might have been said at an earlier date for applying the ex post facto Clause, it has been the unbroken rule of this Court that it has no application to deportation.

We are not prepared to deem ourselves wiser or more sensitive to human rights than our predecessors, especially those who have been most zealous in protecting civil liberties under the Constitution, and must therefore under our constitutional system recognize congressional power in dealing with aliens, on the basis of which we are unable to find the Act of 1950 unconstitutional. See Bugajewitz v. Adams, 228 U. S. 585, and Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 U. S. 276, 259 U. S. 280. [...]

If someone tried to use the Trans-Pacific Partnership to facilitate mass migration into the United States, by executive decision, that would be a totally unconstitutional interpretation, and the Supreme Court of the United States would be obligated to strike down that command at once.

Furthermore, far from allowing the President of the United States to make decisions on his own about the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the TPA arrangement in fact subjected the executive branch to congressional oversight:

S.995 - Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015:

A BILL

To establish congressional trade negotiating objectives and enhanced consultation requirements for trade negotiations, to provide for consideration of trade agreements, and for other purposes.

[...]

(c) International Trade Commission assessment.—

(1) SUBMISSION OF INFORMATION TO COMMISSION.—The President, not later than 90 calendar days before the day on which the President enters into a trade agreement under section 3(b), shall provide the International Trade Commission (referred to in this subsection as the “Commission”) with the details of the agreement as it exists at that time and request the Commission to prepare and submit an assessment of the agreement as described in paragraph (2). Between the time the President makes the request under this paragraph and the time the Commission submits the assessment, the President shall keep the Commission current with respect to the details of the agreement.

(2) ASSESSMENT.—Not later than 105 calendar days after the President enters into a trade agreement under section 3(b), the Commission shall submit to the President and Congress a report assessing the likely impact of the agreement on the United States economy as a whole and on specific industry sectors, including the impact the agreement will have on the gross domestic product, exports and imports, aggregate employment and employment opportunities, the production, employment, and competitive position of industries likely to be significantly affected by the agreement, and the interests of United States consumers.

(3) REVIEW OF EMPIRICAL LITERATURE.—In preparing the assessment under paragraph (2), the Commission shall review available economic assessments regarding the agreement, including literature regarding any substantially equivalent proposed agreement, and shall provide in its assessment a description of the analyses used and conclusions drawn in such literature, and a discussion of areas of consensus and divergence between the various analyses and conclusions, including those of the Commission regarding the agreement.

(4) PUBLIC AVAILABILITY.—The President shall make each assessment under paragraph (2) available to the public.

[...]

That was a bill that was forcing the executive branch to report to the congressional committees on every economic, environmental, and social issue that could be imagined, so that they could keep track of what the executive branch was doing and provide criticisms and make objections.

Rather than being some kind of nefarious scheme, it in fact invited oversight just like any other trade bill that had preceded it in the United States.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership helps to correct global imbalances

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) lights a spark that can facilitate actual economic growth which would raise the living conditions of people in the poorest regions of Asia. It also helps in the process of ‘global rebalancing’. Global structural imbalances and the geographically-based trade deficit, comprise the root of the previous economic crises. Deals like the TPP are economically sound because they are part of the ongoing process of fixing this persistent problem.

Stockhammer (2012) explains:

Stockhammer, E. (2012). ‘Rising Inequality as a Root Cause of the Present Crisis’, PERI, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Working Paper Number 282:

Since the early 1980s an increase in inequality has occurred in all OECD countries. At first sight, this seems to have taken on different forms in different countries. In the Anglo Saxon countries we observe a sharp increase in personal income inequality. Top incomes have experienced a spectacular growth (Piketty und Saez 2003, 2007; OECD 2008). Since 1980 the top income percentile has increased its share in national income by more than 10 percentage points. In continental European countries we see a strong decline in the functional distribution of income. Since 1980 the (adjusted) wage share has fallen by around 10 percentage point (of national income). Given the extent of redistribution that has taken place, one might expect that there are macroeconomic effects. While several authors have noticed that there might be a link between rising inequality and the crisis (Stiglitz 2010, Wade 2009, Rajan 2010), there is as of yet little systematic analysis. This article gives a conceptual framework, based on post-Keynesian theory, for the different channels through which rising inequality may have contributed to the crisis and, secondly, presents some preliminary evidence to substantiate these channels.

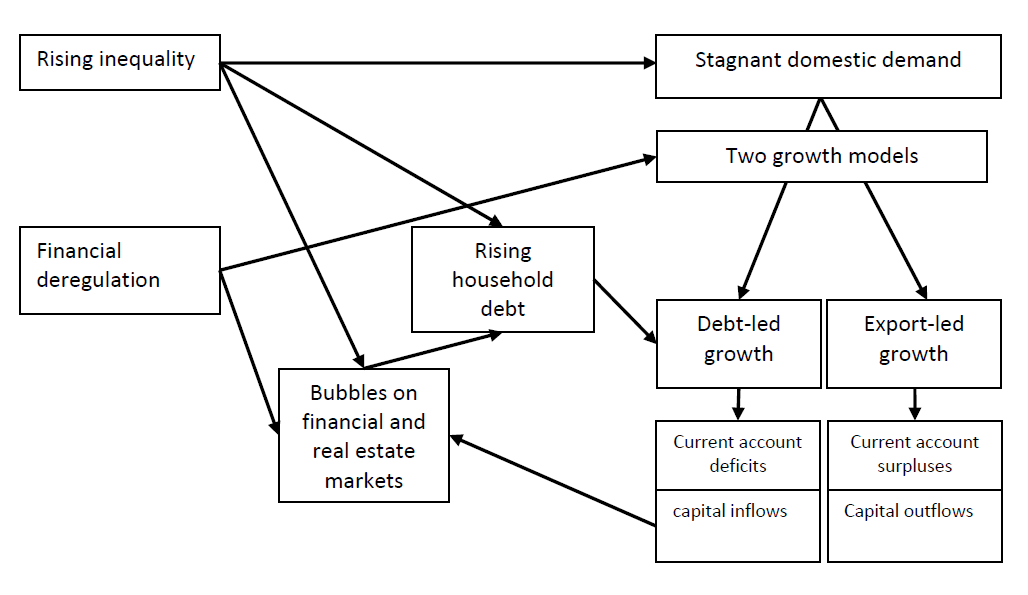

Our hypothesis is that the crisis should be understood as the interaction of the deregulation of the financial sector (or financialisation, more generally) with the effect of rising inequality. In a nutshell our story is the following: since the early 1980s the rise of Neoliberalism has brought about important economic and societal changes, including the deregulation of the financial sector and various legislative measures that have weakened organised labour and the welfare state. From a macroeconomic point of view two growth models have emerged: a debt-led growth model and an export-led growth model.

The USA and the UK are prime examples of the former, Germany and China for the latter. Both growth models can be regarded as a reaction to the lack of domestic demand due to rising inequality. Potentially stagnating domestic demand is compensated for, in the first case, by debt-financed consumption and residential investment booms and, in the second case, by export demand. Several macroeconomic imbalances have emerged: growing trade imbalances across countries; rising household debt levels, namely in the debt-led economies; a rise in the size of the financial sector relative to others; and a rise of asset and property prices. These imbalances are at the root of the crisis. They have been facilitated by financial deregulation, but most of them are intrinsically linked to the rise of inequality.

The paper takes a view that is informed by Kaleckian macroeconomics and by French Regulation Theory. We identify four channels through which rising inequality has contributed to the crisis. Firstly, rising inequality creates a downward pressure on aggregate demand, since it is poorer income groups that have high marginal propensities to consume. Second, international financial deregulation has allowed countries to run large current account deficits and for extended time periods. Thus, in reaction to potentially stagnant domestic demand two growth models have emerged: a debt-led model and an export-led model. Third, (in the debt-led growth models) higher inequality has led to higher household debt as working class families have tried to keep up with social consumption norms despite stagnating or falling real wages. Fourth, rising inequality has increased the propensity to speculate as richer households tend to hold riskier financial assets than other groups.

[...]

This paper has investigated the question whether rising inequality has contributed to the imbalances that erupted in the present crisis, in other words, whether rising inequality is a cause of the crisis. We have discussed four channels through which inequality may have contributed.

This is not to be understood as an alternative to financial factors, but as a complementary explanation that highlights the interaction of financial and social factors.

First, increasing inequality leads potentially to a stagnation of demand, since lower income groups have higher consumption propensity. Second, countries developed two alternative strategies to deal with this shortfall of demand.

In the English-speaking countries (and in Mediterranean countries), a debt-led growth model emerged, in contrast with the export-led growth model in countries such as Germany, Japan or China. These two growth models became feasible because financial liberalisation of international capital flows allowed for unprecedented international imbalances.

Third, in debt-led countries rising inequality contributed to the growth of debt as the poor have increased their debt levels relative to income faster than the rich. For the USA this can be clearly seen in debt-to-income ratios for different income groups. Financialization has meant debt growth instead of wage growth. This growth model that is not sustainable.

Fourth, increasing inequality has increased the propensity to speculate, i.e. it has led to a shift to more risky financial assets. One particular aspect of these developments is that subprime derivatives, the segment where the financial crisis broke out in 2008, were developed to cater to the demands of hedge funds that manage the assets of the superrich. Increasing inequality has thus played a role in the origin of the imbalances that erupted in the crisis as well as in the demand for the very assets in which the crisis broke out.

Our conclusion is that increasing inequality, in interaction with financial deregulation, should be seen as root causes of the crisis. Figure 6 summarises our argument graphically.

This argument has direct implications for economic policy. A broad consensus exists that financial reform is necessary to avert similar crises in the future (even if little has yet changed in the regulation of financial markets). The analysis here highlights that income distribution will have to be a central consideration in policies dealing with domestic and international macroeconomic stabilisation.

The avoidance of crises similar to the recent one and the generation of stable growth regimes will involve simultaneous consideration of income and wealth distribution, financial regulation and aggregate demand. It is this first element “the distribution of income and wealth” that has not conventionally been incorporated in macroeconomic analysis. Put more bluntly, creating a more equal society is not an economic luxury that can be taken care of after the real issues, such as financial regulation, have been sorted out. Rather, a far more equitable distribution of income and wealth than presently exists would be an essential aspect of a stable growth regime: wage growth is a precondition of an increase in consumption that does not rely on the growth of debt. And financial assets are less likely to be used for speculation if wealth is more broadly distributed.

A more equitable distribution of income and wealth will involve changes in tax as well as in wage policy. Reformed tax policies will include increases in upper income tax rates, rises in wealth taxes and the closure of tax loopholes and of tax havens (Shaxson 2011). In the area of wage policy far reaching changes are necessary. Present policy prescriptions aim at cutting wages in a recession. But higher wage growth is a necessary aspect of a balanced economy. It can only be achieved by strengthening of labour union and collective bargaining structures.

As FDI into Asia increases, and as the development of productive forces continues, and as wages in Asia continue to rise, the structural imbalance is ameliorated as populations in these countries gain the ability to actually buy the products which they are manufacturing, rather than selling most of the products as exports to the North Atlantic where they are then purchased by Americans and Europeans on credit.

Taking steps toward breaking that vicious and unsustainable cycle, is one of the most encouraging aspects of the recent developments in Asia.

The transformation which is associated with this rebalancing, was forecasted a while ago:

The National Bureau of Asian Research, ‘Strategic Asia 2012-13’, Oct 2012:

The presence of this new order—which hinged on the military capabilities of the United States—would progressively nurture a new economic order as well, one that began through deepened trading relationships between the United States and its allies but slowly extended to incorporate neutrals and even erstwhile and potential rivals—to the degree that they chose to participate in this order. [...] it maintained a remarkable degree of military advantage despite Soviet opposition, while at the same time sustaining an open economic system at home and an open trading system abroad, both of which interacted to permit the United States and its close allies to grow at a rate much faster than the autarkic economies of its opponents.

The fact that the United States’ allies were able to regenerate their national power so quickly after the devastation of World War II was also a testament to the enlightened elites in these countries: they consciously pursued economic strategies that enabled their nations to make the best of the open economic order that the United States maintained in its interest but which provided collective benefits. The rise of these allies, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and eventually the smaller Southeast Asian “tigers,” undoubtedly portended the relative decline of the United States. But such a decline was judged acceptable because these were friendly states threatened by common enemies, and their revival was judged—correctly—to be essential for the larger success of containment. [6]

Yet the ascendancy of these allies signaled a serious problem that marks all imperial orders, namely, that success produces transformations that can lead to their undoing.

As development of productive forces takes place, and as countries in Asia become more economically powerful, so too will the governmental structures of those countries gain the ability to set up viable regional organisations which would have economic and military clout behind them, a process which is already taking place.

Rather than producing the ‘increasingly globalised world’ that liberals had hoped for, it will instead produce a phenomenon known as ‘deglobalisation’. Deglobalisation is actually just a word that really can be said to describe the growth of a ‘new regionalism’, it is the new way of organising pan-nationalist hegemonic power. It involves new ways of governing, to achieve prosperity and maintain stability:

UNU Global Seminar ‘96, ‘Globalization, the New Regionalism and East Asia’, Björn Hettne, 06 Sep 1996:

1. Whereas the old regionalism was formed in a bipolar Cold War context, the new is taking shape in a multipolar world order. The new regionalism and multipolarity are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. The decline of US hegemony and the breakdown of the Communist subsystem created a room-for-manoeuvre, in which the new regionalism could develop. It would never have been compatible with the Cold War system, since the “quasi-regions” of that system tended to reproduce bipolarity within themselves. This old pattern of hegemonic regionalism was of course most evident in Europe before 1989, but at the height of the Cold War discernible in all world regions. There are still remnants of it here in East Asia.

2. Whereas the old regionalism was created “from above” (often through superpower intervention), the new is a more spontaneous process from within the regions, where the constituent states now experience the need for cooperation in order to tackle new global challenges. Regionalism is thus one way of coping with global transformation, since most states lack the capacity and the means to manage such a task on the “national” level.

3. Whereas the old regionalism was inward oriented and protectionist in economic terms, the new is often described as “open”, and thus compatible with an interdependent world economy. However, the idea of a certain degree of preferential treatment of countries within the region is implied in the idea of open regionalism. How this somewhat contradictory balance between the principle of multilateralism and the more particularistic regionalist concerns shall be maintained remains somewhat unclear. I would myself rather stress the ambiguity between “opened” and “closed” regionalism.

4. Whereas the old regionalism was specific with regard to its objectives (some organizations being security oriented, others economically oriented), the new is a more comprehensive, multidimensional process. This process includes not only trade and economic development, but also environment, social policy and security, just to mention some imperatives pushing countries and communities towards cooperation within new types of regionalist frameworks.

5. Whereas the old regionalism was concerned only with relations between nation states, the new forms part of a global structural transformation in which non-state actors (many different types of institutions, organizations and movements) are also active and operating at several levels of the global system.

In sum, the new regionalism includes economic, political, social and cultural aspects, and goes far beyond free trade. Rather, the political ambition of establishing regional coherence and regional identity seems to be of primary importance. The new regionalism is linked to globalization and can therefore not be understood merely from the point of view of the single region. Rather it should be defined as a world order concept, since any particular process of regionalization in any part of the world has systemic repercussions on other regions, thus shaping the way in which the new world order is being organized. The new global power structure will thus be defined by the world regions, but regions of different types.

It could be said that the Trans-Pacific Partnership is not a push toward increasing globalisation, but rather, can be seen as a response to the rise in international importance of states in the intermediate zones and the periphery which are acquiring a regional identity, and which are increasingly pursuing economic development which is planned from a regional perspective. These states have not only resources and labour power, as well as strong companies and centres of innovation, but also a keen sense of their own identity and the need to use political clout on the world stage in order to defend it.

For countries in South East Asia and in Central and South America, a political will which arises out of the common aspirations of all nations, has combined with geostrategic and economic expediency to make membership in the Trans-Pacific Partnership a very productive move. South East Asian companies and states are confident in their ability to compete in their own way and with their own regional development goals in mind.

Economic power precedes geopolitical power, and a high coefficient of productivity always denotes the reserve capability for a high coefficient of destructive military force. The dispersal of this economic power into the intermediate zones and the periphery, will serve to create a multipolar world—a new world order—in which no single region will be able to arbitrarily determine what is ‘right’ and what is ‘wrong’, and no single region will be able to claim to be the single repository of all political ‘truth’.

In light of the distressing and frustrating things which have happened since 1945 in monopolar or dipolar world orders, all the different initiatives that characterise the beginnings of a transition toward this kind of multipolar world order, in my view should be hailed as a progressive development, and those leaders who—either accidentally or deliberately—have made it possible should be regarded with the deepest appreciation.

Kumiko Oumae works in the defence and security sector in the UK. Her opinions here are entirely her own.

Posted by the black family on Wed, 07 Oct 2015 07:54 | #

It is, of course, highly relevant to WN that this will reduce reasons for Asians to immigrate to Europe and the United States.

Though I am not clear on how industrialization in the Philippines, for example, will much reduce their pursuit of lucrative American health care jobs/professions - fields in The US which they occupy in abundance.

As for those jobs created in Asia, good though that may be for Asian workers and families, won’t it hurt American workers and families?

Daivd Duke is especially concerned about the black family - he is always expressing his concern about the black family, saying how nice that blacks used to be when their families were intact back in the 50s and early 60s. What is going to happen now to the black American family? Imagine how much worse-off the black family is going to be for all of this?

What is going to happen to Detroit?