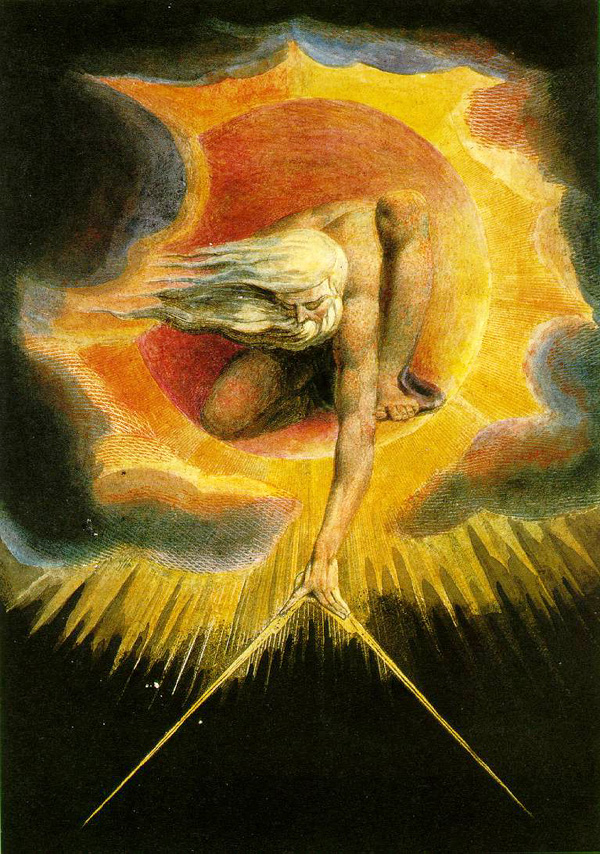

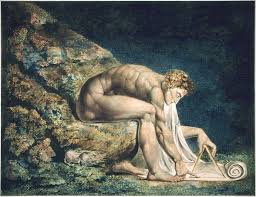

“Wise men see outlines and therefore they draw them”

“Wise men see outlines and therefore they draw them”

D: Don’t be silly. I can’t draw a conversation. I mean things.

F: Yes—I was trying to find out just what you meant. Do you mean “Why do we give things outlines when we draw them?” or do you mean that the things have out-lines whether we draw them or not?

D: I don’t know, Daddy. You tell me. Which do I mean?

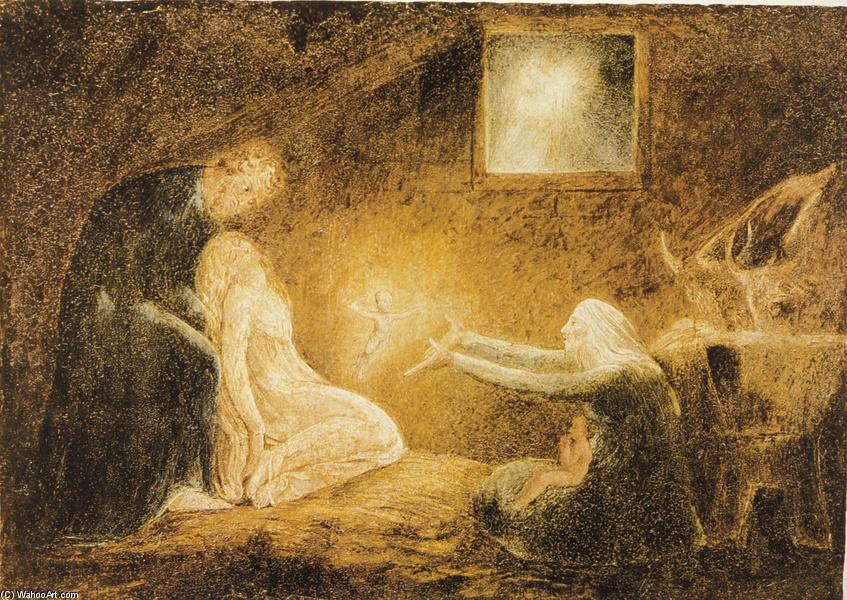

F: I don’t know, my dear. There was a very angry artist once who scribbled all sorts of things down, and after he was dead they looked in his books and in one place they found he’d written “Wise men see outlines and therefore they draw them” but in another place he’d written “Mad men see outlines and therefore they draw them.”

D: But which does he mean? I don’t understand.

F: Well, William Blake—that was his name—was a great artist and a very angry man. And sometimes he rolled up his ideas into little spitballs so that he could throw them at people.

D: But what was he mad about, Daddy?

F: But what was he mad about? Oh, I see—you mean “angry.” We have to keep those two meanings of “mad” clear if we are going to talk about Blake. Because a lot of people thought he was mad—really mad—crazy. And that was one of the things he was mad-angry about. And then he was mad-angry, too, about some artists who painted pictures as though things didn’t have out-lines. He called them “the slobbering school.”

D: He wasn’t very tolerant, was he, Daddy?

F: Tolerant? Oh, God. Yes, I know—that’s what they drum into you at school. No, Blake was not very tolerant. He didn’t even think tolerance was a good thing. It was just more slobbering. He thought it blurred all the outlines and muddled everything—that it made all cats gray. So that nobody would be able to see anything clearly and sharply.

D: Yes, Daddy.

F: No, that’s not the answer. I mean “Yes, Daddy” is not the answer. All that says is that you don’t know what your opinion is—and you don’t give a damn what I say or what Blake says and that the school has so befuddled you with talk about tolerance that you can-not tell the difference between anything and anything else.

“Wise men see outlines and therefore they draw them”

D: Don’t be silly. I can’t draw a conversation. I mean things.

F: Yes—I was trying to find out just what you meant. Do you mean “Why do we give things outlines when we draw them?” or do you mean that the things have out-lines whether we draw them or not?

D: I don’t know, Daddy. You tell me. Which do I mean?

F: I don’t know, my dear. There was a very angry artist once who scribbled all sorts of things down, and after he was dead they looked in his books and in one place they found he’d written “Wise men see outlines and therefore they draw them” but in another place he’d written “Mad men see outlines and therefore they draw them.”

D: But which does he mean? I don’t understand.

F: Well, William Blake—that was his name—was a great artist and a very angry man. And sometimes he rolled up his ideas into little spitballs so that he could throw them at people.

D: But what was he mad about, Daddy?

F: But what was he mad about? Oh, I see—you mean “angry.” We have to keep those two meanings of “mad” clear if we are going to talk about Blake. Because a lot of people thought he was mad—really mad—crazy.

And that was one of the things he was mad-angry about. And then he was mad-angry, too, about some artists who painted pictures as though things didn’t have out-lines. He called them “the slobbering school.”

D: He wasn’t very tolerant, was he, Daddy?

F: Tolerant? Oh, God. Yes, I know—that’s what they drum into you at school. No, Blake was not very tolerant. He didn’t even think tolerance was a good thing. It was just more slobbering. He thought it blurred all the outlines and muddled everything—that it made all cats gray. So that nobody would be able to see anything clearly and sharply.

D: Yes, Daddy

.

F: No, that’s not the answer. I mean “Yes, Daddy” is not the answer. All that says is that you don’t know what your opinion is—and you don’t give a damn what I say or what Blake says and that the school has so befuddled you with talk about tolerance that you can-not tell the difference between anything and anything else.

Text from “Metalogue: Why do Things Have outlines?” (metalogue between father and daughter), Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 1972, p. 37, originally published 1953.