Science Mag, “Meet the frail, small-brained people who first trekked out of Africa, 22 Nov 2016:

On a promontory high above the sweeping grasslands of the Georgian steppe, a medieval church marks the spot where humans have come and gone along Silk Road trade routes for thousands of years. But 1.77 million years ago, this place was a crossroads for a different set of migrants. Among them were saber-toothed cats, Etruscan wolves, hyenas the size of lions—and early members of the human family.

Here, primitive hominins poked their tiny heads into animal dens to scavenge abandoned kills, fileting meat from the bones of mammoths and wolves with crude stone tools and eating it raw. They stalked deer as the animals drank from an ancient lake and gathered hackberries and nuts from chestnut and walnut trees lining nearby rivers. Sometimes the hominins themselves became the prey, as gnaw marks from big cats or hyenas on their fossilized limb bones now testify.

“Someone rang the dinner bell in gully one,” says geologist Reid Ferring of the University of North Texas in Denton, part of an international team analyzing the site. “Humans and carnivores were eating each other.”

What was it that allowed them to move out of Africa without fire, without very large brains? How did they survive?

Donald Johanson, Arizona State University

This is the famous site of Dmanisi, Georgia, which offers an unparalleled glimpse into a harsh early chapter in human evolution, when primitive members of our genus Homo struggled to survive in a new land far north of their ancestors’ African home, braving winters without clothes or fire and competing with fierce carnivores for meat. The 4-hectare site has yielded closely packed, beautifully preserved fossils that are the oldest hominins known outside of Africa, including five skulls, about 50 skeletal bones, and an as-yet-unpublished pelvis unearthed 2 years ago. “There’s no other place like it,” says archaeologist Nick Toth of Indiana University in Bloomington. “It’s just this mother lode for one moment in time.”

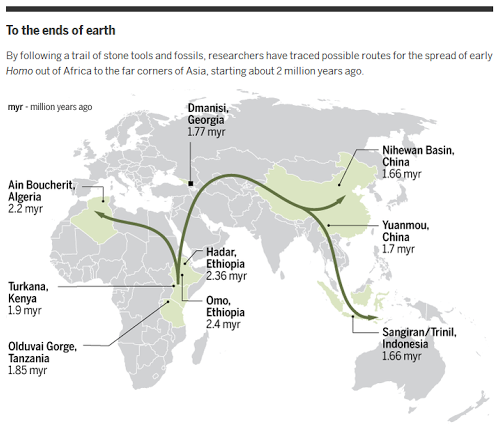

Until the discovery of the first jawbone at Dmanisi 25 years ago, researchers thought that the first hominins to leave Africa were classic H. erectus (also known as H. ergaster in Africa). These tall, relatively large-brained ancestors of modern humans arose about 1.9 million years ago and soon afterward invented a sophisticated new tool, the hand ax. They were thought to be the first people to migrate out of Africa, making it all the way to Java, at the far end of Asia, as early as 1.6 million years ago. But as the bones and tools from Dmanisi accumulate, a different picture of the earliest migrants is emerging.

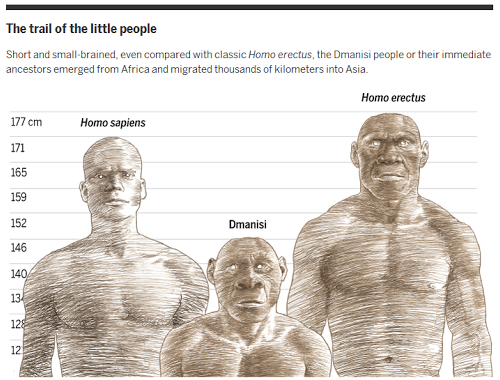

By now, the fossils have made it clear that these pioneers were startlingly primitive, with small bodies about 1.5 meters tall, simple tools, and brains one-third to one-half the size of modern humans’. Some paleontologists believe they provide a better glimpse of the early, primitive forms of H. erectus than fragmentary African fossils. “I think for the first time, by virtue of the Dmanisi hominins, we have a solid hypothesis for the origin of H. erectus,” says Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

This fall, paleontologists converged in Georgia for “Dmanisi and beyond,” a conference held in Tbilisi and at the site itself from 20–24 September. There researchers celebrated 25 years of discoveries, inspected a half-dozen pits riddled with unexcavated fossils, and debated a geographic puzzle: How did these primitive hominins—or their ancestors—manage to trek at least 6000 kilometers from sub-Saharan Africa to the Caucasus Mountains? “What was it that allowed them to move out of Africa without fire, without very large brains? How did they survive?” asks paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson of Arizona State University in Tempe.

They did not have it easy. To look at the teeth and jaws of the hominins at Dmanisi is to see a mouthful of pain, says Ann Margvelashvili, a postdoc in the lab of paleoanthropologist Marcia Ponce de León at the University of Zurich in Switzerland and the Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi. Margvelashvili found that compared with modern hunter-gatherers from Greenland and Australia, a teenager at Dmanisi had dental problems at a much younger age—a sign of generally poor health. The teen had cavities, dental crowding, and hypoplasia, a line indicating that enamel growth was halted at some point in childhood, probably because of malnutrition or disease. Another individual suffered from a serious dental infection that damaged the jawbone and could have been the cause of death. Chipping and wear in several others suggested that they used their teeth as tools and to crack bones for marrow. And all the hominins’ teeth were coated with plaque, the product of bacteria thriving in their mouths because of inflammation of the gums or the pH of their food or water. The dental mayhem put every one of them on “a road to toothlessness,” Ponce de León says

[...]

Regardless of the Dmanisi people’s precise identity, researchers studying them agree that the wealth of fossils and artifacts coming from the site offer rare evidence for a critical moment in the human saga. They show that it didn’t take a technological revolution or a particularly big brain to cross continents. And they suggest an origin story for first migrants all across Asia: Perhaps some members of the group of primitive H. erectus that gave rise to the Dmanisi people also pushed farther east, where their offspring evolved into later, bigger-brained H. erectus on Java (at the same time as H. erectus in Africa was independently evolving bigger brains and bodies). “For me, Dmanisi could be the ancestor for H. erectus in Java,” says paleoanthropologist Yousuke Kaifu of the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo.

In spite of the remaining mysteries about the ancient people who died on this windy promontory, they have already taught researchers lessons that extend far beyond Georgia. And for that, Lordkipanidze is grateful. At the end of a barbecue in the camp house here, he raised a glass of wine and offered a toast: “I want to thank the people who died here,” he said.